Sacred Sailors

September 19, 2016 · 0 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

Japan’s first animated feature was a masterpiece of propaganda film-making, uncompromising in the bile it directed at the enemy, romantic in its evocation of home and hearth and of imperial Japan’s Pan-Asian aspirations, and still unsettling today in its depiction of the mindset of the Japanese military. Its survival to reach modern audiences is itself an adventure story in which it somehow evades bombing raids, burial, shredding and bonfires, emerging from hiding after almost 40 years to offer modern audiences a horrifying glimpse of a very different world.

Japan’s first animated feature was a masterpiece of propaganda film-making, uncompromising in the bile it directed at the enemy, romantic in its evocation of home and hearth and of imperial Japan’s Pan-Asian aspirations, and still unsettling today in its depiction of the mindset of the Japanese military. Its survival to reach modern audiences is itself an adventure story in which it somehow evades bombing raids, burial, shredding and bonfires, emerging from hiding after almost 40 years to offer modern audiences a horrifying glimpse of a very different world.

Japan’s “Fifteen Years War” from 1931-45 created a boom time for the movie industry, particularly after the banning of foreign films in 1939. Japanese film-makers not only filled the vacuum with earnest propaganda, but also gained additional, lucrative contracts to make instructional films for the military. These films are now entirely lost, and including such racy titles as Essentials of Torpedo Maintenance and The Radio Wave Detection Device. Sometimes “90% animated”, the most notorious was probably Principles of Bombardment, used to train the pilots who attacked Pearl Harbor.

The Imperial Japanese Navy became an unlikely patron of the arts, throwing money into films to push the message that Japan was fighting a just war. Producers were immensely pleased with themselves to have made a 37-minute cartoon in which a group of cartoon animals attacked “Devil Island” (a thinly disguised Pearl Harbor) in 1943, only to be trumped by China’s Wan brothers, who released the truly feature-length Princess Iron Fan that same year. Determined to win the war in the cultural arena as well as on the battlefield, the Japanese Navy swiftly drafted the animator Mitsuyo Seo to make a longer film. Puffed up with imperial pride, it was intended to encourage Japanese youths to consider a career in the Navy.

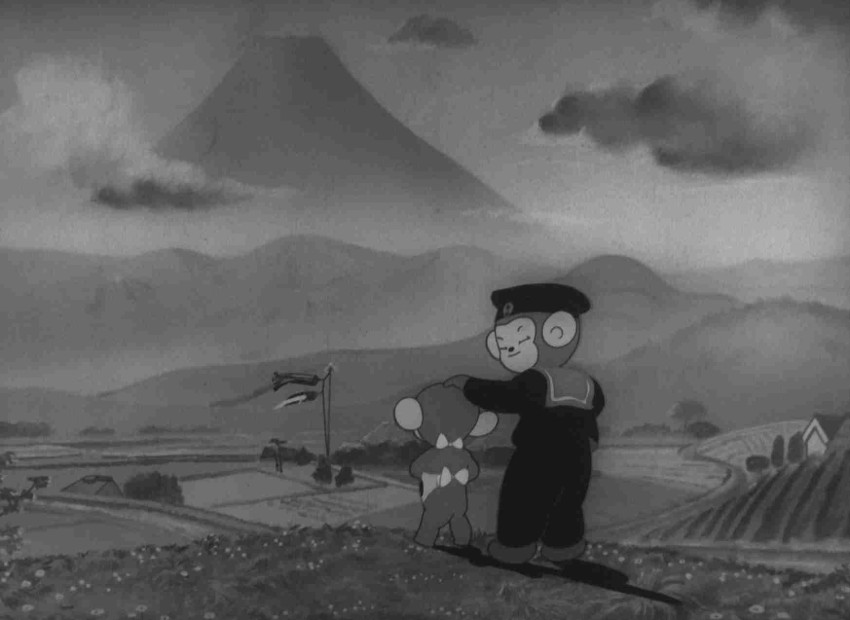

The result was Momotaro Umi no Shinpei (Momotaro’s Divine Sea Warriors, billed in its forthcoming Funimation rerelease as Momotaro, Sacred Sailors), in which the Japanese folk hero Momotaro leads a task force to rescue the peace-loving animals of the South Seas. After their send-off from Japan, they arrive in the Asian jungle where they teach the locals how to sing the Japanese alphabet. In a briefing before their mission, Momotaro explains the history of Western imperialism in Asia, and tells his troops that it is their destiny to liberate the Orient from the white man. They then set off to attack an outpost of British “devils” on the far side of the island – who wave a white flag and then spend the rest of the film refusing to admit who has responsibility for actually surrendering. You know, like Brexit.

The result was Momotaro Umi no Shinpei (Momotaro’s Divine Sea Warriors, billed in its forthcoming Funimation rerelease as Momotaro, Sacred Sailors), in which the Japanese folk hero Momotaro leads a task force to rescue the peace-loving animals of the South Seas. After their send-off from Japan, they arrive in the Asian jungle where they teach the locals how to sing the Japanese alphabet. In a briefing before their mission, Momotaro explains the history of Western imperialism in Asia, and tells his troops that it is their destiny to liberate the Orient from the white man. They then set off to attack an outpost of British “devils” on the far side of the island – who wave a white flag and then spend the rest of the film refusing to admit who has responsibility for actually surrendering. You know, like Brexit.

Seo’s film was an incredible accomplishment, made under wartime deprivations, lacking resources and skilled workers. He resorted to washing his own animation cels with acid to reuse them, destroying the original artwork even as the film was created, and leading to increasingly murky frames as the materials became grubby and cels buckled. Despite restrictions on budget and time, Seo somehow found the time to evoke the poetic imagery of paratroopers as falling dandelions, threw in a song to make it educational and uncompromising silhouette animation for his why-we-fight briefing scene. He also drew on the real world, not only in a pastiche of the surrender of Singapore, but in strikingly realistic depictions of the technology and tensions of a parachute drop.

The film faced problems with its soundscape. Lacking English-speaking foley artists for the big battle scene, Seo instead ripped audio from any foreign films that came to hand, which perhaps explains why you can hear someone suddenly calling for a taxi in the middle of an ambush. A mystery remains as to the identity of the native English speaker who plays the snivelling enemy general – could it be that Japanese animation’s first English voice actor was a prisoner of war?

Despite the heroic efforts in finishing the production on schedule, the film’s release in April 1945 was a disaster. With Tokyo already in bombing range from Pacific islands, most children had been evacuated to the countryside, and young teenagers conscripted to work in factories. Even if they had made it outside through a curfew, the chances of them finding a cinema still standing were remote.

Ironically, one of the first principles that united the Japanese and the newly arrived Allied Occupation forces was their distaste for wartime propaganda. Japanese film-makers, many of whom had entered the industry in order to avoid the draft, feared that they would be prosecuted and censured for collaborating with the military. Nor was this mere paranoia, with over a million subjects returning to Japan from the fallen empire, there was fierce competition over jobs in the film industry, now significantly smaller after the loss of wartime contracts; witch-hunts were common. Some of the first casualties were the many female animators who had worked on 1940s movies, swiftly squeezed out by crowds of demobbed menfolk. But the films themselves also suffered: shredded by the Japanese studios, or burned in great bonfires by the Occupation forces.

Ironically, one of the first principles that united the Japanese and the newly arrived Allied Occupation forces was their distaste for wartime propaganda. Japanese film-makers, many of whom had entered the industry in order to avoid the draft, feared that they would be prosecuted and censured for collaborating with the military. Nor was this mere paranoia, with over a million subjects returning to Japan from the fallen empire, there was fierce competition over jobs in the film industry, now significantly smaller after the loss of wartime contracts; witch-hunts were common. Some of the first casualties were the many female animators who had worked on 1940s movies, swiftly squeezed out by crowds of demobbed menfolk. But the films themselves also suffered: shredded by the Japanese studios, or burned in great bonfires by the Occupation forces.

As the animator Soji Ushio remembered: “Anything reminiscent of the wartime era, anything that reeked of connections to the military, was either shredded or burned and buried. Anything considered harmful by the Occupation authorities was fair game for destruction. I was disconsolate when I heard that films I had put my heart into, and animation I had completed with new technology, these treasures had been buried in a deep pit.” As for Mitsuyo Seo, he returned to his pre-war vocation as a left-wing film-maker, creating the ill-fated The King’s Tail in 1949, a film regarded as so “Red” in the Cold War era that it was banned by the studio that had ordered it. He became a children’s book illustrator, and never worked in animation again.

The Momotaro movie was believed lost for several decades, until a forgotten copy was unearthed in a Japanese film warehouse in 1983. That, at least, is the official story – rumours persist that this priceless print was actually found in an American archive and brought back to Japan to be “discovered” in its birthplace.

Momotaro Umi no Shinpei made it onto VHS in 1984 and a remastered Blu-ray edition only this year. It sees its UK premiere at Scotland Loves Anime, a full 71 years after its completion. Ironically, since it has never been screened in Britain before, it meets the qualifications for consideration as a “new” film for the jury prize, competing against more recent works made by and for the grandchildren of its original creators.

Jonathan Clements is the author of Anime: A History. Momotaro Umi no Shinpei had its UK premiere at Scotland Loves Anime this October, and is screening at the London International Animation Festival on 4th December. It will be released on UK Blu-ray in the New Year.

anime, Japan, Mitsuyo Seo, Momotaro, propaganda, Sacred Sailors, Scotland Loves Anime, Umi no Shinpei, WW2

Leave a Reply