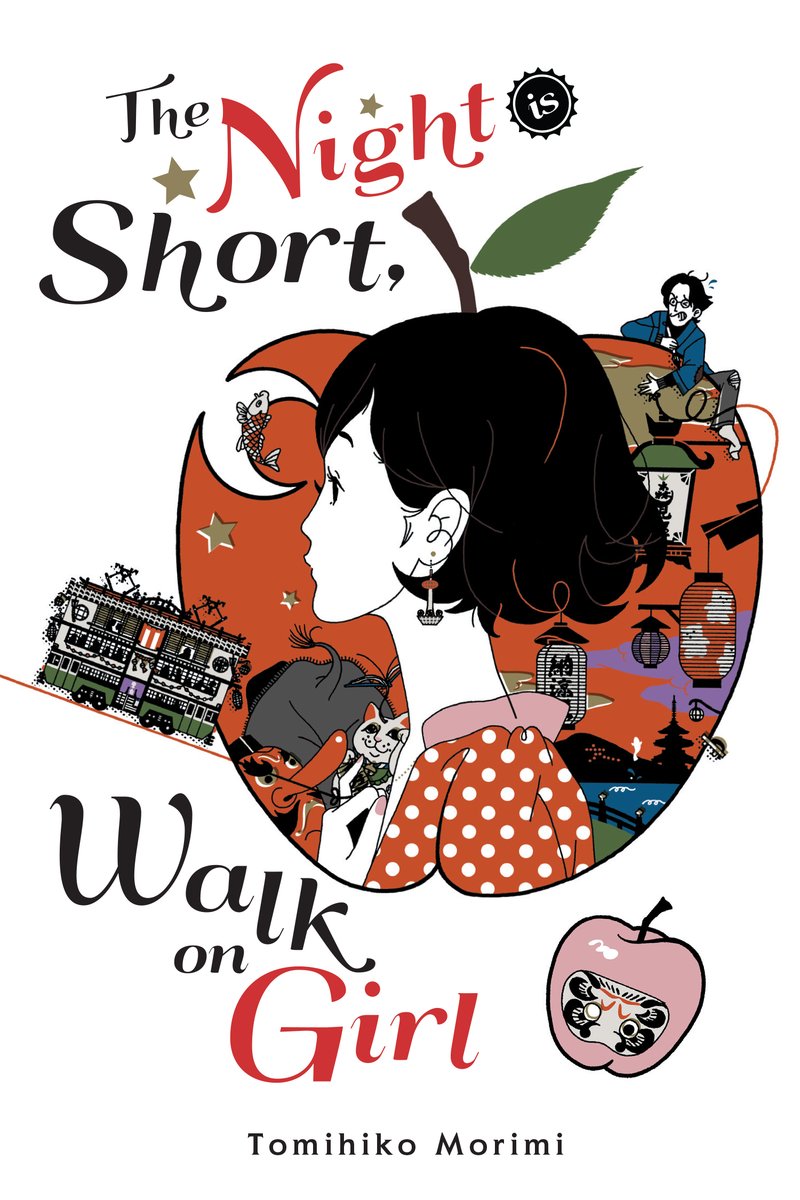

Books: The Night is Short, Walk on Girl

August 27, 2019 · 3 comments

By Jonathan Clements.

“Senpai” adores the Dark-Haired Girl hopelessly. She has no idea. So he follows her around, for a whole year, hoping she will notice him. He tells you his story, but she also tells you hers, as they are slowly brought together in a magical city that once spent a thousand years as the centre of the world.

“Senpai” adores the Dark-Haired Girl hopelessly. She has no idea. So he follows her around, for a whole year, hoping she will notice him. He tells you his story, but she also tells you hers, as they are slowly brought together in a magical city that once spent a thousand years as the centre of the world.

They, like everyone else in the former Japanese capital of Kyoto, are gate-crashers at a never-ending party, browsers in a bookshop where everything is connected, mere mortals wondering if there is any way they can avoid an inevitable tornado of surprised fish dropping out of the sky. I used to live in Kyoto; it is a bit like that.

Author Tomihiko Morimi is famously enamoured with Kyoto, but The Night is Short, Walk on Girl has to be the pinnacle of his adoration, a book-length love letter to the city, told through the reveries of a couple who are seemingly meant for each other. Before long, the Dark-Haired Girl is consorting with a magic-realist menagerie of characters who claim to be crow-demons, who might be fallen Zen monks, who are connected in some out-of-phase, Gaiman-esque way to a faery-realm that overlaps the human world. Meanwhile, someone has stolen our hero’s pants.

In terms of speech, there is little difference between the two characters. They are both diffident prisoners of social obligation, searching for some little, private moment of rebellion. This is either a subtle, romantic indicator that they are kindred spirits, or the mark of an author who can only write in one voice. Fortunately, both Morimi’s narrators are charming innocents, taking their first steps into an adult world that comes laden with wonderful promise. Is there really a secretive cabal of smut collectors in the Kyoto shadows? Could there be a God of Used Book Fairs? How do you placate the God of Colds?

In terms of speech, there is little difference between the two characters. They are both diffident prisoners of social obligation, searching for some little, private moment of rebellion. This is either a subtle, romantic indicator that they are kindred spirits, or the mark of an author who can only write in one voice. Fortunately, both Morimi’s narrators are charming innocents, taking their first steps into an adult world that comes laden with wonderful promise. Is there really a secretive cabal of smut collectors in the Kyoto shadows? Could there be a God of Used Book Fairs? How do you placate the God of Colds?

In recent years, many a script doctor has sneered at the idea that a female character is “pretty but doesn’t know it” – what was once a short-hand for womanly confidence has become a much-derided cliché of dude-bro writing. But our nameless narrator begins the very first tale by recusing himself. He is not the protagonist. This is not his story. That, he claims, belongs to Her in all her glory, and he is merely a dumbstruck worshipper, enraptured by everything about her.

Your mileage may vary. Neither our original narrator nor the all-important Girl have names. She’s just the Girl, the thing he wants, which, in the words of Scritti Politti, means that it’s “a name for what you lose, when it was never yours.” To be fair, she doesn’t give him a name, either, but people-watching, the act of many a flaneur, might be all right in Victorian novels, but carries with it in the woke 21st century an element of stalking. Our hero might think it’s perfectly benign to follow his love interest around town, but that’s the first chapter of either a romance or the story of a serial killer.

He is a laconic, self-deprecating literary inheritor of Haruki Murakami, glumly sitting through a stranger’s wedding. He has a novelist’s yen for the romantic, observing newlyweds kissing, “unafraid of any gods”, and a modernist’s lack of interest in setting the scene – Morimi loves Kyoto with every fibre of his being, but his text largely expects the mere mention of place-names to fill in the pictures, as if everybody knows what Demachiyanagi looks like.

It’s not the fault of translator Emily Balistrieri that Morimi expects nouns alone to carry a sense of place in many Kyoto settings – something, at least, that Masaaki Yuasa’s anime version could impart more effectively for foreign viewers. It is an editorial decision, and probably a wise one, not to add explicatory detail to the original prose, but if any book required some consideration of the implied reader, it was surely this. I was a little taken aback at the lack of footnotes or even an epilogue, pointing to some of the allusions dropped in Morimi’s text, not merely to his own other works, but to historical and mythical characters. When a character grabs a Daruma from a shelf, the reader is expected to know what a Daruma is – I know otaku readers fancy themselves as cultural sophisticates, but please cut the general public some slack! When Rihaku, the wine-soaked king of Kyoto’s wainscot society, slurs the epigram that gives the book its title: “the night is short, walk on girl”, I wonder how many readers will have realised that his name is the Japanese pronunciation of Li Bai, the famous Chinese poet and drunkard?

Chitoseya, the restaurant that seems to straddle Kyoto’s contending cultures like a party that never ends, literally means the Restaurant of a Thousand Years, but you would need to be able to read Japanese to know that, and if you could read Japanese, you wouldn’t need this translation in the first place. I laughed out loud at a girl fronting a band belting out a song called “Piss Off, Benzaiten, you punk!” but I suspect I was probably on my own in a thousand-mile radius.

Chitoseya, the restaurant that seems to straddle Kyoto’s contending cultures like a party that never ends, literally means the Restaurant of a Thousand Years, but you would need to be able to read Japanese to know that, and if you could read Japanese, you wouldn’t need this translation in the first place. I laughed out loud at a girl fronting a band belting out a song called “Piss Off, Benzaiten, you punk!” but I suspect I was probably on my own in a thousand-mile radius.

This is a book about the time your mate Dave got into a drinking competition with a man called Shakespeare in a pub by the Thames that seemed to be mainly populated by fairies. For a Japanese readership, it has all the resonances that we see modern fantasists aspiring to in the likes of Carnival Row or American Gods, but the Yen Press edition displays a remarkable confidence that the average reader overseas will not require any help understanding that. The result is a joyful book that nevertheless needs to be read, at very least, in tandem with the vibrant anime version to fill in the visuals, and probably with an encyclopaedia somewhere close at hand. Is there a God of Encyclopaedias?

Jonathan Clements is the author of A Brief History of Japan. The Night is Short, Walk on Girl is available as a book from Yen Press, and as a film from Anime Limited.

I'm not sophisticate.

August 27, 2019 7:44 am

I empathize with your opinion. It is awkward but I didn't understand 'Gaiman-esque' at first time. What it indicates is arts of Neil Gaiman's sense, isn't it? I read this book in Japanese. I think part of the narrative in this book has akin to magic realism. Has that sense of wonder translated and reproduced in English?

Jonathan Clements

August 27, 2019 8:05 am

*Some* of the sense of wonder certainly transfers across, but that's the problem. I really think that in order to get the maximum enjoyment out of this book, you need to already speak Japanese to some extent, which makes me question the degree to which the translation is a "success". The translator has ably rendered the text in English, but in my opinion, this book really could have done with, at the very least, some extra materials to help overseas readers appreciate what they were getting. There's no easy answer, because you could equally argue that novels shouldn't require extra material to help their readers understand them -- she has done her job, which was to turn the book into English, but I question whether the publisher has packaged that translation in the best way to reach its likely fanbase. I think there are many similarities to Neil Gaiman's work, as I noted in the entry on Morimi in the Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: "Parallels are inevitable with Haruki Murakami, not the least for Morimi's shared penchant for nameless, slacker protagonists and pixie-dreamgirl muses, but in Morimi's work the city itself becomes a nest for Club Stories, the tellers of which may or may not realize that they are living amid the Ruins and Futurity of a forgotten Japan. In that regard, his work might be better regarded as a Japanese answer to the urban fantasies of Neil Gaiman."

I'm not sophisticate.

August 28, 2019 3:56 am

Thank you, Jonathan. Until you suggest a point of view, I haven't noticed a common structure between Morimi's works and Haruki Murakami's works! Because I've thought Morimi's characters are more eccentric and pristine than Murakami's, while Murakami's characters are more mature but little bit neurotic than Morimi's. But these differences are only surface. They exactly have a same structure. However, that is why it is more important for Morimi's works to have a sense of wonder and humor. If his peculiar overtones were swept away from the work, Morimi's narrative would be a aridity and dull. Unfortunately, according to your survey, finished work doesn't seem very good. I agree with your opinion. The translator did the best, but the publisher should have given more consideration as possible. Off the topic: I think Murakami's narrative looks like hard-boiled detective story. Of course, the genre is an author's favorite. and based on your theory, Morimi's works also isn't far from the format.