Japan Box Office Report 2015

February 17, 2016 · 0 comments

Jasper Sharp on the state of the cinema arts

Yes, it’s that time again when the Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan (better known by the abbreviated Japanese name of Eiren) releases its box office figures for the previous year. I’ve already put down my analyses and thoughts about what kind of barometer these provide for the overall health of the industry for the 2013 and 2014 statistics, and superficially at least, 2015 seems to follow the usual pattern of business booming on the home front.

Yes, it’s that time again when the Motion Picture Producers Association of Japan (better known by the abbreviated Japanese name of Eiren) releases its box office figures for the previous year. I’ve already put down my analyses and thoughts about what kind of barometer these provide for the overall health of the industry for the 2013 and 2014 statistics, and superficially at least, 2015 seems to follow the usual pattern of business booming on the home front.

Overall admissions are up 3.4% from 166.1 million to 166.6 million, and total box office has similarly risen from 207 billion yen to 217.1 billion yen (equivalent to $1.84 billion), with this slightly higher 4.9% growth in takings attributable to a 1.4% rise in average ticket prices from 1,285 Yen to 1,303 Yen. (These percentages are cited from Gavin J. Blair’s overview of the 2015 Japanese Box Office for The Hollywood Reporter).

Neither figure is quite as high as the 2010 peak of 174.4 billion admissions and gross box-office receipts of 220.7 billion yen – this boom year not only received a significant boost from Avatar and the new wave of 3D releases that accompanied it (including Disney-Pixar’s Toy Story 3 and Up and Tim Burton’s Alice in Wonderland), but also such domestic hits as Studio Ghibli’s Arrietty and the latest theatrical instalments of the live-action Umizaru and Bayside Shakedown TV tie-ins. Nevertheless, they do demonstrate the sustained growth of the exhibition sector since the inevitable post-Avatar slump of 2011. Indeed, 2015 represents one of the industry’s healthiest years of the 21st century, at least in economic terms.

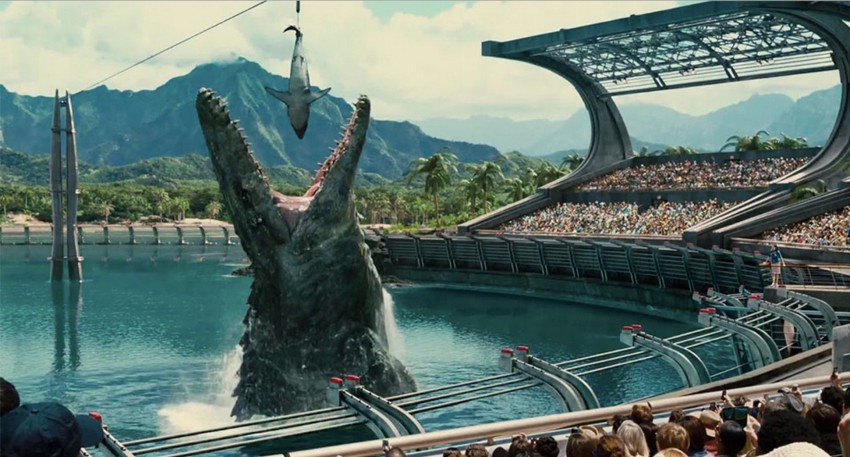

While pundits in Europe and America are increasingly looking at the growth of video-on-demand and other non-theatrical revenue streams within their domestic accounting, the figures released by Eiren deal exclusively with the theatrical sector. So for example, while we can see that the top-grossing non-Japanese title from last year, Jurassic World, earned an estimated 9.53 billion yen, this figure is derived entirely from cinema ticket sales. There is no indication anywhere in the report what amount the subsequent DVD, Blu-ray or streaming releases would have added to its overall revenues in Japan – nor indeed any of the 1,136 titles distributed in Japanese cinemas in 2015. And presumably there are straight-to-video titles or films circulated in other non-theatrical forms not accounted for at all here.

While pundits in Europe and America are increasingly looking at the growth of video-on-demand and other non-theatrical revenue streams within their domestic accounting, the figures released by Eiren deal exclusively with the theatrical sector. So for example, while we can see that the top-grossing non-Japanese title from last year, Jurassic World, earned an estimated 9.53 billion yen, this figure is derived entirely from cinema ticket sales. There is no indication anywhere in the report what amount the subsequent DVD, Blu-ray or streaming releases would have added to its overall revenues in Japan – nor indeed any of the 1,136 titles distributed in Japanese cinemas in 2015. And presumably there are straight-to-video titles or films circulated in other non-theatrical forms not accounted for at all here.

Meanwhile, although cinema-going in Japan has been viewed as a comparatively expensive pastime, with the current average ticket price of 1303 yen equating to £7.70 (or approximately $11) at today’s exchange rate, this price hasn’t actually risen that much since 2000, when it was 1,262 yen. That’s a 3.2% ticket rise in 15 years. Now compare this with the United Kingdom, where the £4.40 average admission of 2000 had risen by 53% to £6.72 in 2014 (currently more than the hourly minimum wage), according to the figures published by the British Film Institute, and it is not difficult to see why so many people have stopped going to the cinema over these very same years that have seen rising attendances in Japan. Indeed, these BFI figures are in themselves open to question. Here, the average ticket cost is calculated by dividing the UK-only box office gross for the year by the total number of UK admissions. However, peak times for the newly-opened Picture Central and Curzon Bloomsbury in London are nearly three times this amount, at a ludicrous £18, tickets cost up to £11.75 at the BFI Southbank itself, and I recently paid £9.30 for a weekday matinee screening at the out-of-town Cineworld in Ashford, Kent.

On the other hand, at the time of writing, the full recommended retail price of the basic Blu-ray of Jurassic World would cost you 4,309 yen in Japan, and about £14.99 in the UK (before store discounting). It is clear why viewers in some countries opt to watch films on the big screen while in others home-viewing is the favoured option.

I draw attention to this issue because nowadays one often hears people talking about the demise of the cinema as the primary point of consumption for both film in general, and specifically the Hollywood product. This is clearly not the case when one looks outside of Europe and North America. Films that exploit those elements unique to the cinema experience – the bigger screen, more immersive sound, added novelties such as 3D and 4D, the communal viewing environment – will continue to be made for viewers in the largest theatrical markets in the world, such as China and Japan, because that is where the largest amount of money is to be made.

Ticket prices and viewing conditions are ultimately determined by cinema exhibitors, and in this respect it is necessary to point out that it was yet another year of near monopoly for Toho in the Japanese market. Unlike so many of its cinema-chain counterparts in other parts of the world, Toho has an incredibly long history not just in exhibition, but also distribution and production. This point is spelled out dramatically by the 12-metre-tall Godzilla head emerging from the new flagship Shinjuku Toho Building, which opened in Kabukicho on 17th April last year.

Ticket prices and viewing conditions are ultimately determined by cinema exhibitors, and in this respect it is necessary to point out that it was yet another year of near monopoly for Toho in the Japanese market. Unlike so many of its cinema-chain counterparts in other parts of the world, Toho has an incredibly long history not just in exhibition, but also distribution and production. This point is spelled out dramatically by the 12-metre-tall Godzilla head emerging from the new flagship Shinjuku Toho Building, which opened in Kabukicho on 17th April last year.

Toho’s newest revolution in film exhibition, the latest step in a more general process of renovation and rebuilding that began with the wholesale switch to digital a few years back, is also symptomatic of the gentrification of the surrounding Kabukicho district, and indeed the entire capital, in the run-up to the 2020 Olympics. Alongside the cinema complex of 12 theatres (presumably all 3D capable) – including one IMAX screen, one installed with the latest 4D technology, one Dolby Atmos sound system (the remainder are all kitted with 5.1 Digital sound) and the largest screen in the country, with an auditorium seating 2,323 viewers – the building also houses a luxury hotel, restaurants, shops and other amusements.

According to a report in Variety, it was at this venue that Jurassic World generated an income of 100 million yen from just one single screen – the one fitted with the MediaMation MX4D system, providing synchronized motion seats and other in-theatre non-sight-and-sound effects such as air and mist sprays.

Two years ago I wrote that in comparison with other Asian countries, 4D technology arrived rather late to Japan, with the first such venue opening in Nagoya on 26th April 2013. This was still ahead of the UK, which got its first 4DX screen on 30th January 2015 at the Cineworld Milton Keynes. Just as Cineworld are getting behind 4D technology in the UK (with new screens now in Crawley, Sheffield and one promised for Birmingham), its rapid proliferation in Japan has been pushed by two major competing chains – United Cinemas, who use the same South Korean-developed 4DX system (featuring nine effects), and Toho, who are pushing the new American MX4D system (with eleven effects). And just as Avatar was the key driver in the switch to 3D some 6 years ago, last year’s rush of 4D installations is largely due to just one title: Star Wars: The Force Awakens.

At the last count, Toho now operates nine MX4D motion effects theatres across Japan, while United Cinemas has eleven 4DX theatres. This difference between the number of screens and the merits of MX4D vis-a-vis 4DX might seem slight, but it is crucial when one is vying for audiences for the biggest film of the year – especially when one considers that the cinemas themselves get to retain a good chunk of the ticket surcharge.

At the last count, Toho now operates nine MX4D motion effects theatres across Japan, while United Cinemas has eleven 4DX theatres. This difference between the number of screens and the merits of MX4D vis-a-vis 4DX might seem slight, but it is crucial when one is vying for audiences for the biggest film of the year – especially when one considers that the cinemas themselves get to retain a good chunk of the ticket surcharge.

Sticking with the subject of cinema chains, while we see the number of screens across Japan up from 2014 by 73 (2.1%) from 3,364 to 3,437, the number of these housed in multiplexes has increased by 85 (from 2,911 to 2,996), which now account for 87.2% of Japan’s total screen count. This suggests that elsewhere there has been a loss of at least 12 single-screen venues. Separate statistics provided by UniJapan show that the number of screens dedicated exclusively to Japanese language films have dropped from 107 in 2010 to 65 in 2014 (the figures aren’t in for 2015 yet), and it is safe to assume that most of these, if not all, would be the adult cinemas specialising in erotic “pink cinema”, which have suffered the most acutely from the switch to digitalisation. Meanwhile, following the great cull of some of Tokyo’s more distinctive cinematic treasures over recent years (Ginza Cine Pathos, Baus Theater, Cinema Rise, Roman Gekijo…), the three-screen Shinjuku Tokyu Milano in Kabukicho, closed its doors on the final day of 2014. Built in 1956 (a year before Tokyo Tower), it was but a stone’s throw away from the new Shinjuku Toho Building.

It is perhaps related to the increasing power of the chains that the overall number of Japanese films released in 2015 is down to 581 from the previous year’s figure of 615. The trouble is that neither Eiren nor UniJapan provide a full list of the titles released in any given year, so it is difficult to surmise what, if any, specific sector of the Japanese industry might account for this decline in overall production (i.e. are there any specific types of films that aren’t being made nowadays). The massive leap in what are labelled “theatrical releases” from 441 in 2011 to its 2014 high was attributable to the rise in ODS (“Other Digital Stuff”), typically live or pre-recorded music or sports events. Hollywood Reporter states that this area “grew nearly 50 percent to $130 million (¥15 billion) last year”, so that’s not certainly not where the source of the decline lies. Nor is it the pink film genre, whose dwindling levels of output already flat-lined some years back.

Elsewhere, the significant trend is that while the box-office share for Japanese films has outweighed that of foreign imports since 2008, it has nevertheless continued to drop since 2012, when it was 65.7% and now stands at 55.4%. Behind the top-earner Jurassic World, with its 9.53 billion yen gross, other top ten titles highlight how animation continues to be big business in Japan. Big Hero 6, which gave more than a passing nod to the anime aesthetic, at the number 2 position took 9.18 billion yen; Minions at number 4 took 5.21 billion Yen; and Inside Out at number 6 took 4.04 billion yen. Again, one doubts Toho are complaining about the erosion of the market for Japanese films, as four of this top ten – Jurassic World, Minions, and the live-action films Fast & Furious 7 (at number 7) and Ted 2 (at number 10) – were distributed by its foreign import subsidiary, Toho-Towa. Walt Disney Studios distributed four of the other top 10 foreign grossers.

Elsewhere, the significant trend is that while the box-office share for Japanese films has outweighed that of foreign imports since 2008, it has nevertheless continued to drop since 2012, when it was 65.7% and now stands at 55.4%. Behind the top-earner Jurassic World, with its 9.53 billion yen gross, other top ten titles highlight how animation continues to be big business in Japan. Big Hero 6, which gave more than a passing nod to the anime aesthetic, at the number 2 position took 9.18 billion yen; Minions at number 4 took 5.21 billion Yen; and Inside Out at number 6 took 4.04 billion yen. Again, one doubts Toho are complaining about the erosion of the market for Japanese films, as four of this top ten – Jurassic World, Minions, and the live-action films Fast & Furious 7 (at number 7) and Ted 2 (at number 10) – were distributed by its foreign import subsidiary, Toho-Towa. Walt Disney Studios distributed four of the other top 10 foreign grossers.

On the domestic side, Toho’s dominance looks even more shocking, with it distributing eight of Japan’s top ten local earners – the exceptions are DRAGON BALL Z Resurrection ‘F’ at number 6 (handled by Toei) and Love Live! The School Idol Movie at number 8 (Shochiku). There’s the customary strong showing for anime, with the usual suspects Detective Conan: Sunflowers of Inferno and Doraemon the Movie: Nobita and the Space Heroes popping up at number 4 and 5. The live-action manga adaptations of Attack on Titan part 1 (at number 7) and Assassination Classroom (at number ten) are also worth noting.

As to be expected, the main absence among the top-ranking domestic releases of this year is Studio Ghibli, although the 5.8 billion yen takings of The Boy and the Beast, positioned at number 2, supports claims for its director Mamoru Hosoda’s status as Hayao Miyazaki’s natural successor in the field of high-quality auteurist-driven animated storytelling. That’s one reason to be cheerful, at least.

As to be expected, the main absence among the top-ranking domestic releases of this year is Studio Ghibli, although the 5.8 billion yen takings of The Boy and the Beast, positioned at number 2, supports claims for its director Mamoru Hosoda’s status as Hayao Miyazaki’s natural successor in the field of high-quality auteurist-driven animated storytelling. That’s one reason to be cheerful, at least.

But let us turn to the occupier of the number one spot, which is listed by Eiren as Yo-Kai Watch the Movie 2: King Enma and the 5 Stories, Nyan! This appears to be a mistake, with its listed release date of December 2014 actually that of Yo-Kai Watch the Movie: It’s the Secret of Birth, Meow! Both films were directed by Shigeharu Takahashi and Shinji Ushiro and belong to a franchise that began with the Yo-Kai Watch Nintendo 3DS roleplaying game in Japan in 2013 and has continued through a number of manga and TV serials. Taking 7.80 billion Yen, this first movie incarnation was the top domestic earner and third highest-grossing release of the year.

Yo-Kai Watch the Movie 2 was the subject of a recent article by Mark Schilling in Variety reporting that the 975,000 tickets sold for its 19th-20th December opening weekend exceeded that of the 800,000 for Star Wars, released in Japan on 18th December, although in terms of box-office revenues it actually earned less (again, think of those surcharges for Stars Wars’s 4D screenings). Both were released too late in the year to be included in the figures for 2015, but no doubt they will be right at the top of next year’s rankings.

Meanwhile, the Yo-Kai Watch anime series has been licensed for broadcast outside Japan, already airing in the U.S, and looks set to become the new Pokemon. However it seems highly unlikely that either film will ever replicate this domestic success in international markets, and ultimately George Lucas has little to fear.

Meanwhile, the Yo-Kai Watch anime series has been licensed for broadcast outside Japan, already airing in the U.S, and looks set to become the new Pokemon. However it seems highly unlikely that either film will ever replicate this domestic success in international markets, and ultimately George Lucas has little to fear.

Indeed, we can say that for most of the top-earning Japanese releases of 2015, and remembering that domestic success has never had much bearing on the type of films from Japan overseas viewers are exposed to, Toho’s near monopoly of the domestic market as both a distributor and an exhibitor are still cause for ongoing concern. When cinema chains have this much control, it not only influences what gets shown, but also what gets made. While there is some solace to be had from the appearance of Hirokazu Kore’eda’s Our Little Sister, positioned at the number 22 spot in the domestic rankings (distributed by Toho), and Takeshi Kitano’s Ryuzo and his Seven Henchmen at 24 (distributed by Japan’s Warner Brothers office), like other national cinemas, the more ambitious mid-budget range of productions are increasingly being lost to a smaller range of bigger films, a winner-takes-all situation where the main victim is diversity.

But the Japanese market seems to go in cycles, where several years of comfortable coasting are suddenly punctuated by crucial developments that hit all at once. Such disruptions have previously occurred in 1954, 1963, 1972, 1997 and 2004. Hopefully we are due for a similar upheaval any time now.

Jasper Sharp is the author of The Historical Dictionary of Japanese Cinema.

Leave a Reply