A Silent Voice: Anime vs Manga

March 13, 2017 · 3 comments

By Andrew Osmond.

Kyoto Animation’s film A Silent Voice comes to British cinemas this week; to learn about its story and characters, see our previous article. However, you don’t need to have seen the film to know the story. At the British premiere at Scotland Loves Anime, the audience was asked how many had read the Silent Voice manga by Yoshitoki Oima. At least half the crowd raised their hands.

Kyoto Animation’s film A Silent Voice comes to British cinemas this week; to learn about its story and characters, see our previous article. However, you don’t need to have seen the film to know the story. At the British premiere at Scotland Loves Anime, the audience was asked how many had read the Silent Voice manga by Yoshitoki Oima. At least half the crowd raised their hands.

A Silent Voice was serialised in Weekly Shonen Magazine, which as its name indicates is “officially” for boys. The magazine shouldn’t be confused with Shonen Jump, its greatest rival, home to One Piece, Naruto, Dragon Ball et al. But Weekly Shonen Mangazine’s own roster of strips spans six decades. Starting in 1959, it published the likes of Gegege no Kitaro, Star of the Giants, Tomorrow’s Joe, Tiger Mask, Devilman, Love Hina and Fairy Tail.

One thing that separates A Silent Voice from these titles is that it’s by a woman. It’s interesting, though, that Yoshitoki Oima has a gender-neutral name. As Silent Voice’s female director Naoko Yamada commented to Neo, many Japanese readers wouldn’t have known Oima is female. Some women artists take ‘neutral’ names for that reason: Hiromi Arakawa, for example, took the pen name of Hiromu to write Fullmetal Alchemist.

One thing that separates A Silent Voice from these titles is that it’s by a woman. It’s interesting, though, that Yoshitoki Oima has a gender-neutral name. As Silent Voice’s female director Naoko Yamada commented to Neo, many Japanese readers wouldn’t have known Oima is female. Some women artists take ‘neutral’ names for that reason: Hiromi Arakawa, for example, took the pen name of Hiromu to write Fullmetal Alchemist.

Interviewed by Kodansha, Oima describes her childhood self as “a tomboy who liked to play imaginary gunfights.” That suggests an affinity with Shoya and Yuzuru in A Silent Voice, though disarmingly Oima says she’s close to a very different character, the bubble-haired Tomohiro. “If Tomohiro was real, I’d want to stay away from him,” Oima comments. (Readers who know the character will understand why.) “But his inner self is very close to mine, in the sense he clings to his friends.”

Oima was eighteen when she wrote the prototype for A Silent Voice, a one-shot manga. It was published in 2008 in Bessatsu Shonen, a spinoff of Weekly Shonen Magazine (and home of Attack on Titan – Oima later contributed illustrations to the TV anime). The one-shot won the Annual Shonen Magazine Newcomer Award, though it’s not included in the English edition of A Silent Voice.

Like many new artists, Oima’s first “pro” assignment after her award was to support an established name. From 2009, she drew Mardock Scramble, written by Tow Ubukata from his grisly SF/horror novels, which were also made into anime. The manga is available in English in seven volumes. I reviewed the first of them, commenting that Oima’s “light,” cartoonish drawn style “makes the violence less brutish, while the lighter moments are cuter… somewhere on the dial between charming and sentimental, with extra blood and bangs.”

The artist herself said Mardock left her no room to express her own voice, and yet it was an inspiration. “In Mardock Scramble,” says Oima, “the main character Balot says she wants to die. As a reader, I didn’t get why, and I wanted to know why. I wanted to dig deeper. What leads a person to think in such way? I felt like it was my duty to really understand this point. The answers I got from working on Mardock Scramble carried through to A Silent Voice.”

The “full” Silent Voice manga began in August 2013 and ran for a little over a year in Weekly Shonen Magazine, with the last chapter (62), published in November 2014. The film adapts the sweep of the 1300-page strip, even as it trims minor or major details to fit a 129-minute runtime. It’s an unusual strategy for anime, where films adapting long manga typically adapt small parts of the strip, reworking the story extensively. (Classic cases include Nausicaa, Akira – both based on strips that were unfinished at the time– and Ghost in the Shell.)

The “full” Silent Voice manga began in August 2013 and ran for a little over a year in Weekly Shonen Magazine, with the last chapter (62), published in November 2014. The film adapts the sweep of the 1300-page strip, even as it trims minor or major details to fit a 129-minute runtime. It’s an unusual strategy for anime, where films adapting long manga typically adapt small parts of the strip, reworking the story extensively. (Classic cases include Nausicaa, Akira – both based on strips that were unfinished at the time– and Ghost in the Shell.)

For the benefit of readers who know Silent Voice already, either from the film or manga, we thought it would be interesting to look at how the story was adapted between media. As many changes concern later scenes, MAJOR SPOILERS follow. All the references are to the collected seven-book English edition, published by Kodansha Comics and translated by Steven LeCroy.

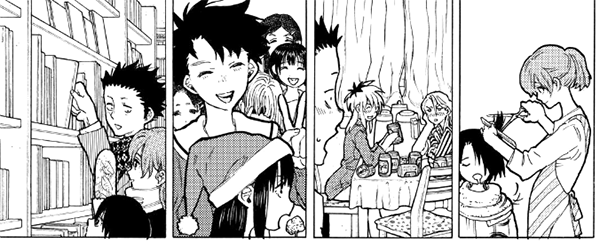

The first four books have the most “detailed” adaptation in the film. The first book, as one might guess, focuses on the elementary school scenes, where Shoya tormented Shoko. The second book introduces Tomohiro and Yuzuru. Book three brings in the teen Miyoko and Naoka, and ends with Shoko’s attempted confession to Shoya. “I lub moo!” is how the translation puts it. However, Yuzuru later teases Shoko by getting her to say Japanese words that sound similar to “suki”, the Japanese for “I love you” – the manga adds a translation note to clarify.

Book four includes the amusement park sequence and the funeral of Shoko’s and Yuzuru’s gran. Book five has the painful breakup of the friends and Shoya’s awkward summer dates with Shoko. The breakup has much more force in the manga; the forced dates, though, work better when sped up in the film. The fifth book ends with the pivotal scene during the summer festival, when Shoya finds Shoko on her balcony, about to fall. All the film’s subsequent scenes are compressed from the last two books; that’s 350-odd manga pages in maybe twenty minutes.

Book four includes the amusement park sequence and the funeral of Shoko’s and Yuzuru’s gran. Book five has the painful breakup of the friends and Shoya’s awkward summer dates with Shoko. The breakup has much more force in the manga; the forced dates, though, work better when sped up in the film. The fifth book ends with the pivotal scene during the summer festival, when Shoya finds Shoko on her balcony, about to fall. All the film’s subsequent scenes are compressed from the last two books; that’s 350-odd manga pages in maybe twenty minutes.

Of course, plenty of details are cut even from the early books. For example, the manga suggests young Shoya is influenced by his never-properly-seen big sister, whose attitude is “Life is a war against boredom.” For his sister, that leads her to having endless boyfriends (thirty, allegedly!), before sticking with the Brazilian Pedro. For Shoya, it shapes his search for diversions, like jumping off bridges or picking on a deaf girl.

There’s also more of an arc for Shoya’s class teacher, which continues through the manga. At first he seems more responsible than he was in the film, lecturing Shoya about his attitude (“You can’t make fun of Nishimiya because of her disability”). Later though, he doesn’t bother keeping his mask in place. “I do understand how you feel,” he mutters to Shoya, when the bullying is well underway. The teacher returns in later books, with our sympathies stacked against him, though it’s suggested that his seeing Shoya and Shoko together teaches him something.

Other manga scenes are reduced to split-second glimpses in the anime. For example, in the film, we briefly see little Shoko and her mother at the hair salon to get Shoko’s hair cut by Shoya’s mum. That’s a trace of a more significant thread in the manga, where Shoko’s mother demands a “boyish” haircut for her daughter to make her more acceptable. Shoko doesn’t want it, and Shoya’s mum backs the child. As well as setting up antagonism between the mums, this leads to Yuzuru adopting a “boyish” look, in order to protect her sister. Later, a long karaoke scene in the manga is boiled down by the film to a clip on a mobile phone.

Other scenes are shifted or combined. The scene where Shoya’s mum forces him to confess he was planning suicide happens early in the film, presumably to make the emotional trajectory smoother. In the manga, it happens after the story has already lightened up. There are other transpositions. In the manga, Shoko jumps into the canal from the bridge (Shoya follows) after her mother throws her notebook in the water. In the film, Shoko’s mother isn’t even in that scene, which the film merges with a different manga scene for good measure.

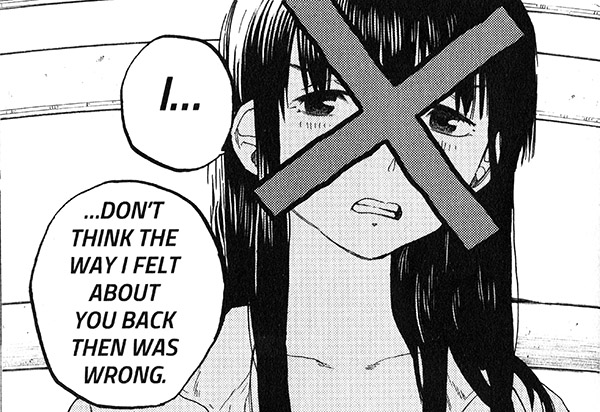

Shoya, Shoko, Tomohiro and Yuzuru are all very similar to the manga counterparts, although some dialogue (at least to my mind) is made less on-the-nose in the film. The manga Shoya declares he wants to “dedicate his life” to Shoko, sounding like he’s read too much Shonen Jump. Shoko says openly that she hates herself (it’s in the film, but easy to miss), and later pours out her feelings to Naoka – of all people! – in a letter. After Shoko’s suicide attempt, Naoka reads out the letter sarcastically before beating Shoko up outside the hospital.

Shoya, Shoko, Tomohiro and Yuzuru are all very similar to the manga counterparts, although some dialogue (at least to my mind) is made less on-the-nose in the film. The manga Shoya declares he wants to “dedicate his life” to Shoko, sounding like he’s read too much Shonen Jump. Shoko says openly that she hates herself (it’s in the film, but easy to miss), and later pours out her feelings to Naoka – of all people! – in a letter. After Shoko’s suicide attempt, Naoka reads out the letter sarcastically before beating Shoko up outside the hospital.

Other characters are trimmed back ruthlessly. To be fair, many of the manga’s key character moments are in flashbacks which would have made the film unwieldy. Many revelations come in book 6, perhaps the strongest part of the manga, which recalls the TV ending of Evangelion. Characters must stand alone and give accounts of themselves as the ongoing story is suspended.

Elsewhere, one of the most powerful manga flashbacks shows the backstory of Shoko’s mother, who was a victim of bullying worse than her daughter’s. Her husband (and his family) rejected her for producing a “defective” child; the scene is so nasty that it might have been cut for that reason alone.

As one would expect, the supporting teen characters – Naoka, Miyoko, Miki and Satoshi – register much more in the manga compared to the film. For instance, it’s made plain that Naoka fancied Shoya at elementary school, therefore Naoka bullied Shoko. Her scary possessiveness of Shoya is pointed up. “Don’t be fooled by Shoko,” she thinks in Shoya’s direction, “men are suckers for quiet, pitiful women like her.” Naoka’s friendship with Miyoko is also highlighted. A big difference from the film: in the manga, Miyoko intervenes in the ugly fight outside the hospital, as the sole character who’s a true friend to both Shoko and Naoka.

The girl Miki, meanwhile, is shown critically and sympathetically at once. The manga suggests her shallow lack of self-awareness doesn’t rule out true kindness, which feels like an act of kindness in itself. It’s Miki’s boyfriend Satoshi who’s cut back most in the film, to the point of being a placeholder. In the manga, he has his own dark issues tied to bullying. Interviewed by Roxy Simons in MyM magazine, director Naoko Yamada says Satoshi’s story was cut because, “I didn’t want a negative storyline like that to drag on in the film.”

An easier cut is the manga plotline about the characters making a student film. It takes up a great deal of space, though its main purpose is to force Shoya to revisit his past. Tomohiro packs him off to his old elementary school to ask if the group can film there, not knowing Shoya’s terrified of the place, for obvious reasons! This plotline develops Satoshi and even Shoya’s old teacher, but it’s still an obvious cut for the film to make.

An easier cut is the manga plotline about the characters making a student film. It takes up a great deal of space, though its main purpose is to force Shoya to revisit his past. Tomohiro packs him off to his old elementary school to ask if the group can film there, not knowing Shoya’s terrified of the place, for obvious reasons! This plotline develops Satoshi and even Shoya’s old teacher, but it’s still an obvious cut for the film to make.

Whereas many of the story’s key scenes play well in either medium, the results are more mixed near the end. The climax on the balcony, for example, is somewhat clunky in the strip, but far more gripping in the film. On the other hand, the sequence where Shoko and Shoya reunite through possibly magical means is the weakest and most damaging part of the film. The manga, though, actually sells it, partly through some bravura graphic storytelling from Shoko’s point of view as she runs frantically into the night. Without any fancy drawing, the strong panel-to-panel storytelling is a match for any anime sakuga.

The film’s ending is another exercise in rearrangement. The film’s very last scene, at the school festival, comes from midway through book seven. However, several later scenes and story points are skilfully shunted back into the final minutes (Pedro, for one). The last manga chapters, after the film ending, have the characters considering where they go after graduation; Shoko finding she can spread her wings; and Shoya alarmed that she might not need him anymore. Regarding the biggest question about “what happens” to the characters, the manga, like the film, declines to give a definite answer. However, the final manga images point clearly in one direction.

Overall, A Silent Voice is an excellent manga and an excellent film; recommendable in either format, and an enjoyably intricate exercise in adaptation if you have time to compare them side by side. Yes, much strong material is lost in the transfer from manga to film, but much is also gained in colour, spectacle and snowballing momentum. And Silent Voice signs loud and clear that there’s never just one way to see the world.

A footnote: Yoshitoki Oima is currently writing what sounds like a very different kind of manga, To Your Eternity, described as “a spiritual fantasy, the tale of an abandoned native boy journeying in the frozen north with only a mysterious wolf for a companion.”

Andrew Osmond is the author of 100 Animated Feature Films. A Silent Voice shows across the UK this Wednesday, and in the Republic of Ireland a little later. The manga is published by Kodansha.

Jordan J

March 16, 2017 1:28 am

Brilliant write up guys. Just got back from watching this and have to say was a fantastic watch. Have just recently read the manga myself and so was great to see this animated even with all the omissions as mentioned above. Thanks again fro bringing this to us and am very much looking forward to the bluray release

Cassidy E

September 30, 2021 10:41 pm

Does the manga include a lot more material or is it pretty much the same as watching the movie cause if there is and I’m missing out I’ll def go ahead and buy the whole set just curious

Andrew Osmond

October 1, 2021 9:27 pm

Hello Cassidy. The manga does have a great deal more material than the film, especially on the supporting characters.